Freud and a Tale of Three Cities: Vienna, London and……. Orvieto.

The Vienna home in Berggasse 19 is easy to spot – he lived and worked in two modest, dark flats on the mezzanine floor left and right of the long red Freud sign; 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, London, is by comparison quite understated, just the round Blue Plaque; Orvieto now has a modest grey plaque to the right of the doorway.

The Vienna flat contains little: his hats and cane, a hip flask used on his travels and the furniture of the waiting room where he held his 8.30 Wednesday evening meetings which Anna Freud returned to Vienna.

Freud lived in Vienna for 47 years, whereas he lived in London for a mere eighteen months till he died an exile just after the outbreak of World War II in 1939, though his daughter Anna lived on in the Freud home in Hampstead for another 40 years.

The London home contains most of his possessions shipped from Vienna before the war. His chair was specially built for him so that he could read with his leg over the arm. The glass jar above the antiquities cabinet contains his and his wife’s ashes. The original Apulian krater with a Dionysiac imagery was smashed by burglars in 2014.

- Freud’s study in London – his reading chair made to his own design so he could hang his leg over the arm.

- Statues of divinities from the ancient world on his desk

- Roman Glass jar containing cremated remains.

- Cremated remains. He had once dreamed of drinking water from a funerary urn in which the water tasted salty. (Interpretation of Dreams 1900)

In Orvieto he never lived at all, but he did stay in the Hotel delle Belle Arti in Corso Cavour 36 in 1897, 1902 and 1907. However, this small Umbrian town was to contribute to the development of his theories quite disproportionately.

The Former Hotel delle Belle Arti in Palazzo Bisenzi (building on right with balcony) where Freud stayed on the main street, Corso Cavour, Orvieto.

Freud admitted to three passions: travelling, archeology and smoking. Freud was an ardent, but anxious, traveller. He did most of his writing while away from Vienna. Italy was his favourite destination, he came here 24 times, seven to Rome alone. Travelling in Italy gave him the freedom and relaxation that he lacked in Vienna which he confessed to his friend Fliess was a city he loathed.

Archeology was more than a hobby, it dovetailed with his delving into the human psyche, in fact he had more archeology books in his library than any other subject. Just before his Orvieto trip he started collecting antique statuettes a hobby that developed in Orvieto when he met Riccardo Mancini who not only offered him newly unearthed antiquities, but invited him to the Etruscan necropolis at the Cimitero del Crocefisso where he preserved a tomb as it had been found with its grave goods and two skeletons. This tomb was to feature in an important dream of Freud’s.

- The Etruscan Cemetery, the tombs built like wooden houses on a street, the names in Etruscan script are above the door

- Interior of house tomb. Freud saw two complete skeletons. He was later to dream he was in this tomb.

Freud’s dream: “I had already been in a grave once, but it was an excavated Etruscan grave near Orvieto, a narrow chamber with two stone benches along its walls, on which the skeletons of two grown men were lying.The inside of the wooden house in the dream looked exactly like it, except that the stone was replaced by wood. The dream seems to have been saying:’If you must rest in a grave let it be the Etruscan now”.

Mancini even offered Freud a plot of land that was guaranteed to give up more Etruscan treasures; after mulling it over a while he declined.

- Doorway in Etruscan tomb opening onto the street

- Orvieto, the Crocefisso cemetery that impressed Freud so much belonged to Sig Mancini who sold him Etruscan antiquities

Freud’s third passion was smoking, twenty-five cigars a day, yet he failed to quit even though he knew it was killing him and causing him terrible pain.

Freud’s father Jacob had died in October 1896, prompting a crisis in Freud’s thinking and writing in early 1897 that was to result in his embarking upon self-analysis, something that no one had ever done before. At around this time, he had also decided on chastity after his youngest and last child Anna (destined to become his intellectual heir) was born December 1895. From 1896 he would sublimate his libido into his mission, psychoanalysis, the term he coined in 1897.

When Freud arrived in September, Orvieto had, until the recent opening of the railway to Rome, been an out of the way place, a Bruges La Morte under an Umbrian sun. Olave Potter in her turn of the century book A Little Pilgrimage in Italy 1911 called the chapter on Orvieto, City of Woe; the Pre-Raphaelite painter Burne-Jones passing through in 1871 thought the people striking to look at, but the saddest looking folk he saw in all Italy.

From the station Freud would have taken the new funicular cable car up the precipitous rock and through the dark tunnel beneath the Albornoz fortress, itself a charged experience for someone of Freud’s sensibility.

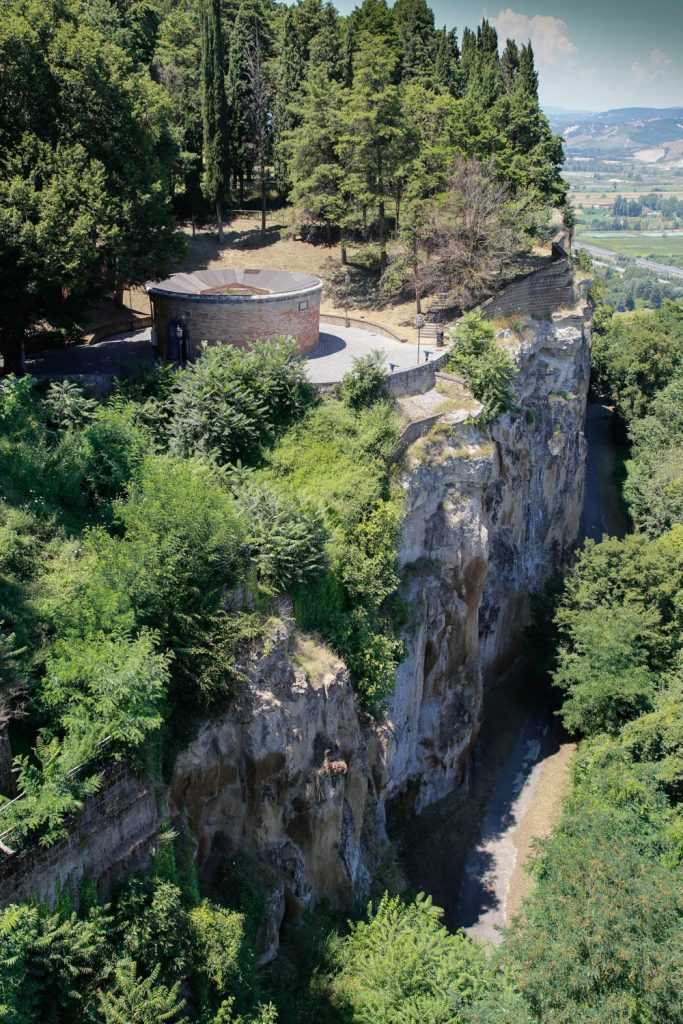

- St Patrick’s well seen from above the funicular

- Orvieto’s funicular railway passing through the tunnel

- Entrance to St Patrick’s Well not 50m from the Funicular station

- Entrance to St Patrick’s Well

Next to the funicular is the 16th century St Patrick’s Well, a tourist attraction mentioned in Freud’s Baedecker guidebook. Although Freud does not mention a visit it is unlikely that he would have passed up such a Dantesque experience on at least one of his sojourns.

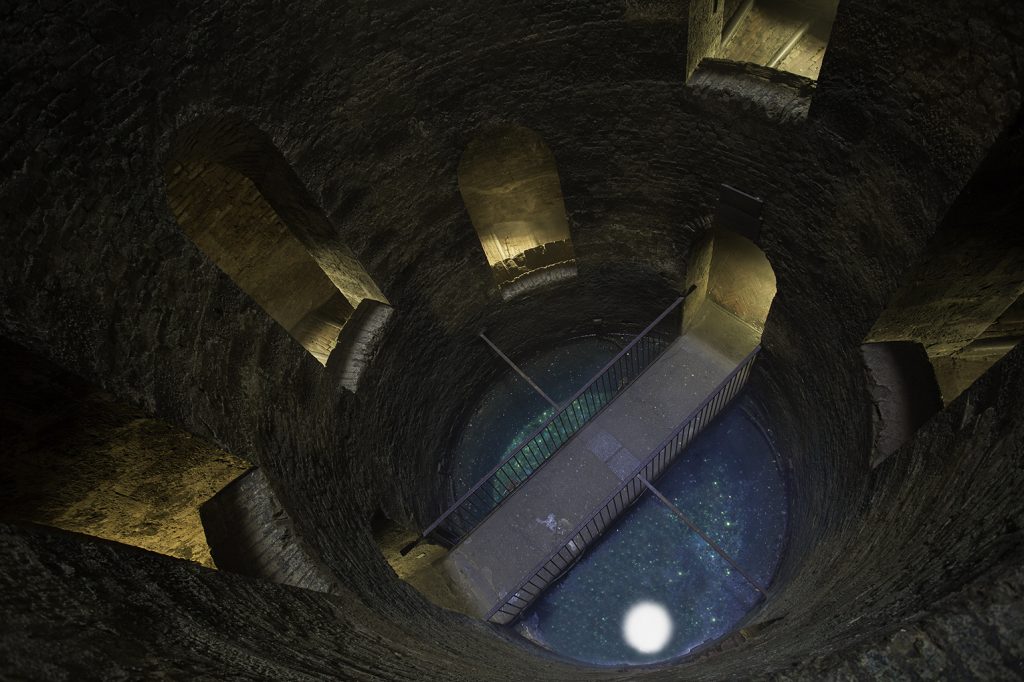

- St Patrick’s Well, built by Sangallo,1527-1537

- a wonder of Renaisance engineering

- Sangallo possibly took the idea of the double helix from Leonardo da Vinci

The well is 62m deep and of a double helix spiral, like DNA, so that the donkey carrying water up did not meet the donkey going down. The increasing gloom during the descent, the marvel of the engineering, the effort of returning to the light up a sort of Jacob’s ladder, the suggestive nature of the spiralling shaft must surely have impressed him; yet he never mentions the well.

Freud though a non-believer was well read in the scriptures and would certainly have known of many references to wells and their importance to a desert people, not least Moses with whom he identified in his quest for a psychoanalytical promised land; indeed, Moses met his wife Zipporah at the Midian well. The commissioner of the well, Pope Clement VII (the one who gave Henry VIII such a hard time over his divorce), also saw himself as a new Moses, having a commemorative medal struck by Cellini showing Moses striking the rock with water gushing forth and the motto ”Ut bibat populous” (for the people to drink).

- St Patrick’s Well from the bridge over the water

- St Patrick’s Well from the bottom looking up – click on this image it’s quite a suggestive view.

- the well’s crystal water 62m below the surface

- The Dantesque stairway leading to the depths

However, the letters he wrote to his wife’s sister Minna Bernays with whom he corresponded in the most intimate manner about his work, vacations and thoughts, are all missing from the period 1893 to 1910, the timespan of his three Orvieto visits. There has been much speculation that Freud and Minna had an affair, even that he procured her an abortion, and that their correspondence may have been occulted or destroyed for this reason.

The well may or not have been important to the formulation of Freud’s theories, but the frescoes in Orvieto Cathedral by the Renaissance artist Luca Signorelli most certainly were.

To be continued……..

[…] post A Tale of Three Cities – Part 1. Freud and a Tale of Three Cities: Vienna, London and……Orvieto appeared first on Camera Etrusca Photography Workshops, Photo Holidays and Tours in […]