The impressive ruins of the Etruscan temple of the Belvedere lie near the funicular station, bounded on one side by St Patrick’s Well and on the other by the road leading out of Orvieto to the Etruscan necropolis of the Cimitero del Crocefisso below the cliffs. Freud would have travelled this road when he visited the necropolis Dating from about 500 BC, it was uncovered during construction of the new road in 1828.

Belvedere Temple, showing outer sanctum, with bases of columns, and the inner sanctum beyond. St Patrick’s well lies behind the trees.

Numerous artefacts were found including the miniature bronze statue of Minerva, now in the Civic/Faina Museum. Freud’s favourite statue, bought some time after 1914, is almost identical, in fact Athena is the Greek Minerva. Freud described her as ‘perfect, only she has lost her spear.’ Freud’s Athena is a Roman copy of a Greek original. She holds a patera, a dish for pouring libations, whereas the Orvieto version carries the aegis cloak over her shoulder. Both have the Medusa breastplate.

The temple was dedicated to the three Capitoline gods: Tinia (Jupiter /Zeus), Uni (Juno/Hera) and Minerva (Athena), most probably on the right side of the sanctum where the tiny statue was found. The temple was constructed almost entirely of wood above the stone podium so little remains, but there would have been a large collonaded portico, the outer sanctum, and then three cellae dedicated to the three gods, the inner sanctum.

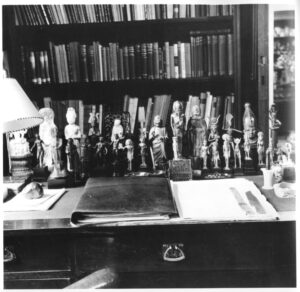

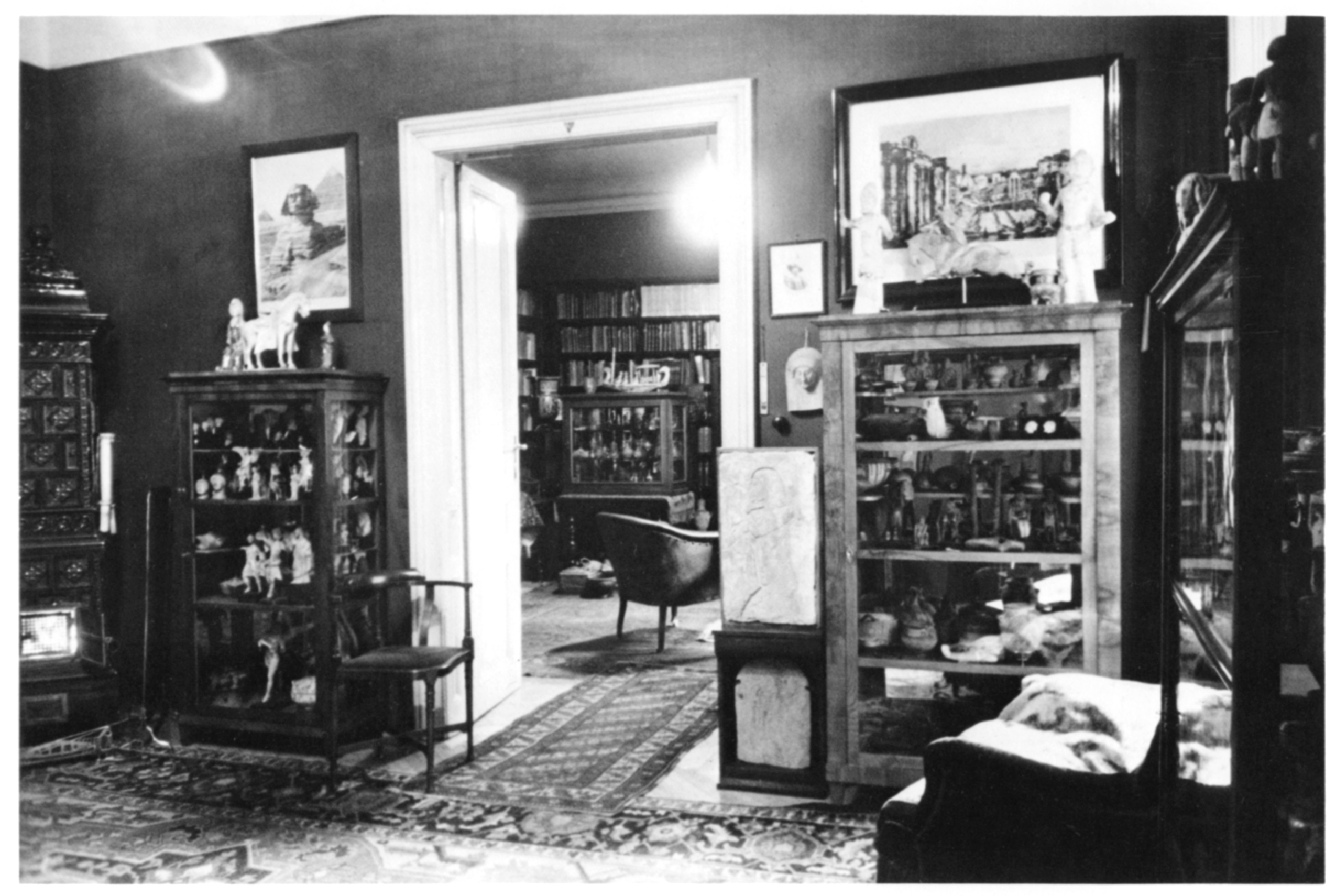

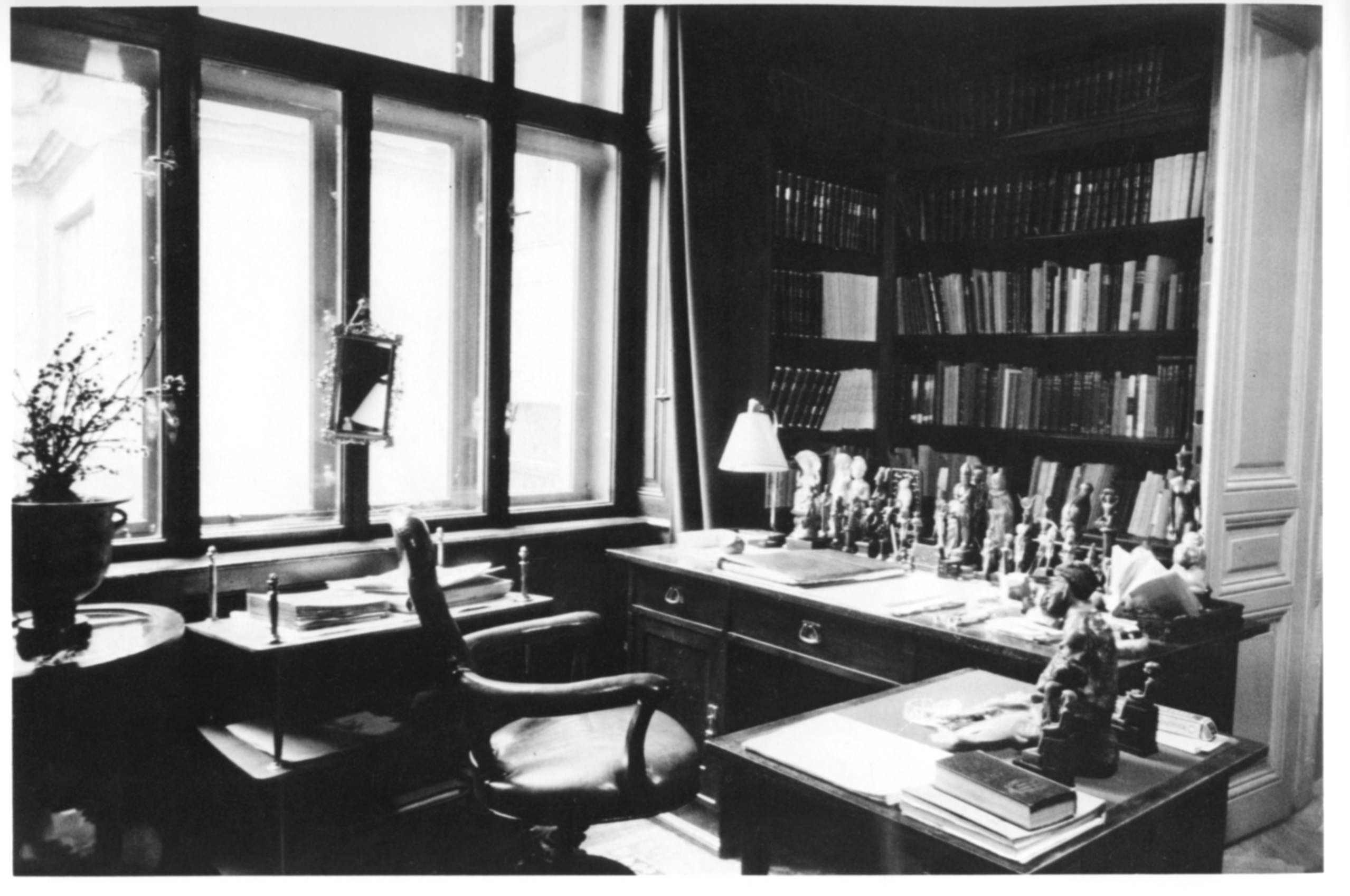

We know that Freud started collecting genuine antiquities, as opposed to replicas, the summer of his first Orvieto visit in 1897, and began to arrange them in his consulting rooms on the ground floor of Berggasse 19. Later he transferred to the floor above, the site of the present museum). As his collection grew he arranged his collection in the manner of the Belvedere Temple, the bulk of his antiquities jostled for space in his outer sanctum, the consulting room, in which he had his famous couch, many concealed in drawers; whereas, the Inner Sanctum, his study held his prize pieces, arranged in cabinets, vitrines, and arrayed across his desk, a small army, mainly of statuettes, all directed towards him, the commander in chief. His temple is estimated to have held around three thousand artefacts although many were donated to friends and colleagues over the years. He had a drawer entirely full of Etruscan bronze mirrors and would ask favoured guests to ‘help themselves.’

Engelman’s view of Freud’s study from his consulting room towards the study, Freud’s ‘inner sanctum’, which gave onto a central courtyard.

Edelman’s famous photographs taken just before the Freuds’ departure for London, clearly show the arrangement in his consulting rooms, by now upstairs, on the mezzanine floor, the entrance across the way from his family’s flat. He complained about the darkness of both flats. As a mezzanine, it was below the massive balconies of the piano nobile, the first-floor flat, which left it gloomy.

Perhaps this dimness, which he oft complained of while doing nothing to lighten it, is why he had need of his nearly three-month-long summer holidays, excursions always accompanied by his terracotta army, painstakingly packed and transported to the shores of Lake Aussee, Bad Gastein, to the Alpine heights at the Riemerlehen in Berchtesgaden, and his summer house in Grinzing in the Wienerwald, the Vienna Woods. He wrote on holiday and was unable to do so without his ‘grubby old gods’.

When Freud visited Orvieto for three nights in 1897 he met Riccardo Mancini, who owned an antiquities emporium on Corso Cavour, a five-minute walk from his hotel, from which Freud began to acquire his own collection.

Mancini called himself an archeologist and had the good fortune to own some rich sites around Orvieto including the famed Etruscan Necropolis of the Crocefisso del Tufo below the cliffs on which the town is built. Mancini’s enormous enthusiasm for archeology, which was not only commercial, no doubt infected Freud, to the point where he collected more books on the subject than he did on psychology. There are obvious parallels between excavating into the ancient past and delving into the unconscious.

Freud returned to Orvieto twice, most likely to further his collaboration with ‘my friend’ Engineer Mancini, who even offered him a plot of land to buy so that he could not only get his hands dirty digging for his own antiquities but export them more easily from Italy.

Freud’s Inner Sanctum, his study in May 1938. His favourite statuette of Athena/Minerva is no longer in the middle of his desk. It had been sent ahead to London in the care of his friend and benefactor Princess Marie Bonaparte, afraid that the Nazis might not allow him to export his collection in its entirety. On the side desk right is an open copy of his favourite magazine, Die Antike. Ph. Edmund Engelman, May 1938.

The same view today, his reading chair in the corner is a replica. The mirror is original. The study was darkly painted in Pompeian style red in 2016; it is now white, not a bit like the sombre tones of Freud’s day. The room beyond is his consulting room in which he had his famous couch. The waiting room is beyond that through the white doors.

Both flats in Berggasse 19 now belong to the Viennese Freud Museum. All the rooms have recently been redecorated in white, quite unlike the sombre coloured apartments of Freud’s day. Most of the furniture is in the London home and museum, though some of the waiting room furniture was donated by the youngest daughter Anna Freud to the Vienna Museum.

In this smoke-filled room he held the weekly meetings of The Wednesday Psychological Society. My photographs were taken before the refurbishment, and I believe, render the atmosphere of Freud’s day rather better than the present-day photos with the trendy white patterned wallpaper which can be seen on the Freud Museum’s website.

Athena comes home to London

London, Freud’s study cum consulting room. The famous couch has temporarily lost its Persian drapes – dry-cleaning. His desk with its statues is on the left.

Freud’s desk in London with Athena-Minerva in pride of place (highlighted). Thoth, the white baboon on the right, another favourite, had his top knot rubbed every morning by Freud.

Freud’s desk in London with Athena-Minerva in pride of place (highlighted). Thoth, the white baboon on the right, another favourite, had his top knot rubbed every morning by Freud.